In unit tests, I favor Detroit over London

•

26 June 2022

•

6 mins

Recall the two schools of thought around unit test: Detroit, and London. Briefly, the Detroit school considers a ‘unit’ of software to be tested as a ‘behavior’ that consists of one or more classes, and unit tests replace only shared and/or external dependencies with test doubles. In contrast, the London school consider a ‘unit’ to be a single class, and replaces all dependencies with test doubles.

| School | Unit | Isolation | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit | Behavior | Replace shared and external dependencies with test doubles | ‘fast’ |

| London | Class | Replace all dependencies (internal, external, shared, etc.) with test doubles | ‘fast’ |

See this note for a more detailed discussion on the two schools.

Each school have it’s proponents and each school of thought has it’s advantages. I, personally, prefer the Detroit school over the London school. I have noticed that following the Detroit school has made my test suite more accurate and complete.

Improved Accuracy (when refactoring)

In the post on attributes of a unit test suite, I defined accuracy as the measure of how likely it is that a test failure denotes a bug in your diff. I have noticed that unit test suites that follow the Detroit school tended to have high accuracy when your codebase has a lot of classes that are public de jour, but private de facto.

Codebases I have worked in typically have hundreds of classes, but only a handful of those classes are actually referenced by external classes/services. Most of the classes are part of a private API that is internal to the service. Let’s take a concrete illustration. Say, there is a class Util that is used only by classes Feature1 and Feature2 within the codebase, and has no other callers; in fact, Util exists only to help classes Feature1 and Feature2 implement their respective user journies. Here although Util is a class with public methods, in reality Util really represents the common implementation details for Feature1 and Feature2.

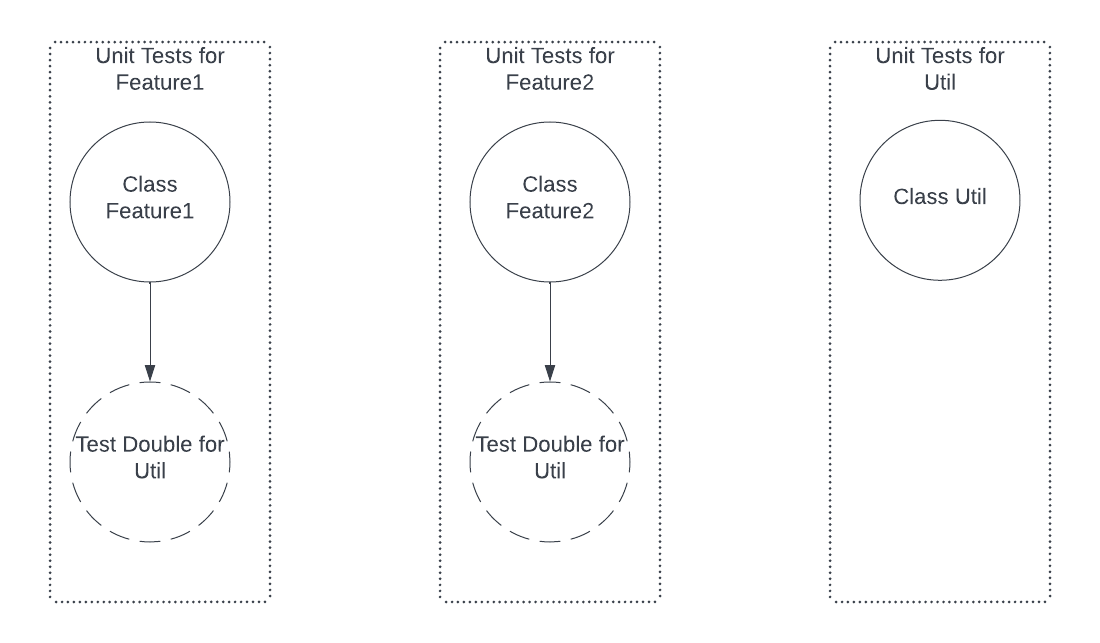

In London

According to the London school, all unit tests for Feature1 and Fearure2 should be replacing Util with a test double. Thus, tests for Feature1 and Feature2 look as follows.

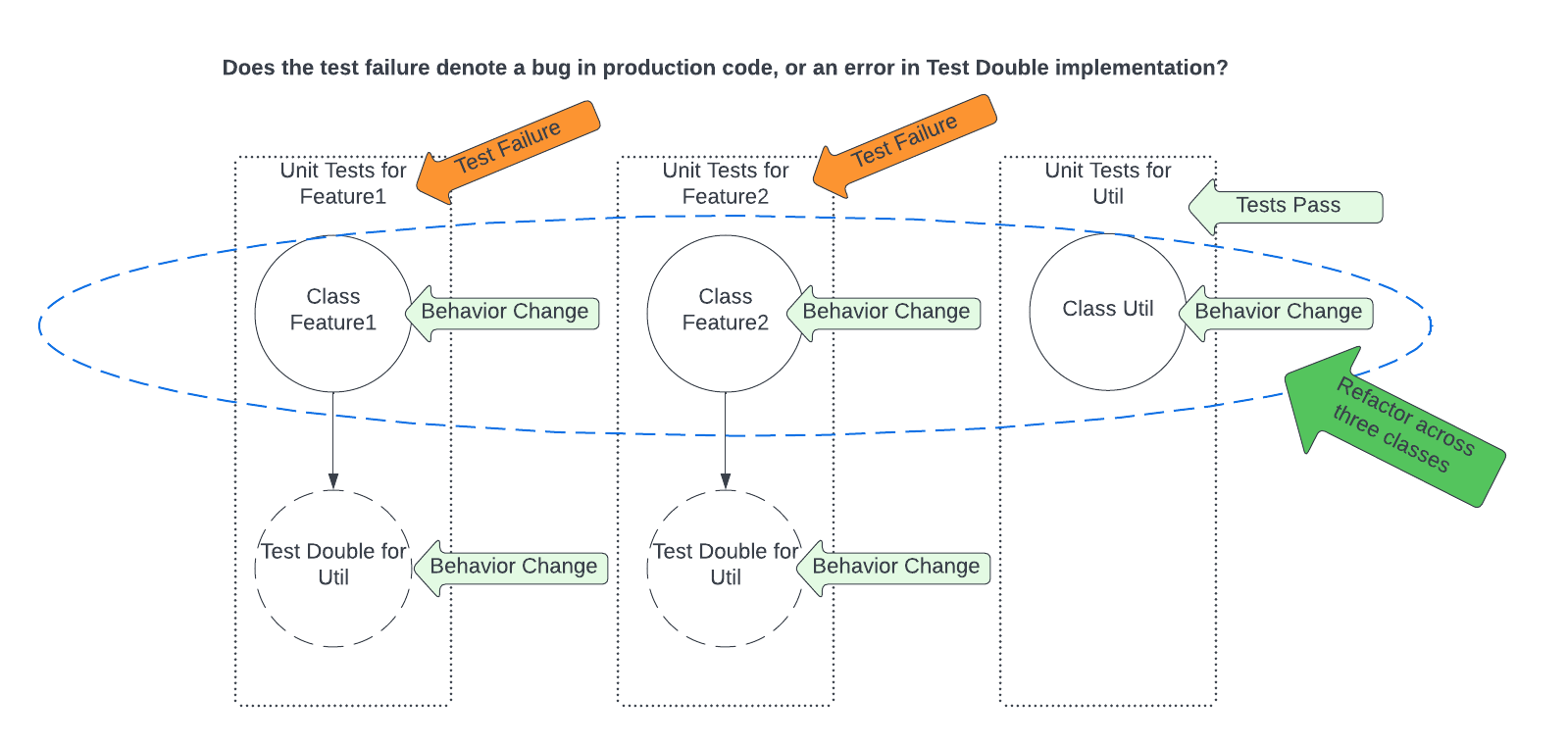

Now, say we want to do some refactoring that spans Feature1, Feature2, and Util. Since Util is really has a private API with Feature1 and Feature2, we can change the API of Util in concert with Feature1 and Feature2 in a single diff. Now, since the tests for Feature1 and Feature2 use test doubles for Util, and we have changed Util’s API, we need to change the test doubles’ implementation to match the new API. After making these changes, say, the tests for Util pass, but the tests for Feature1 fail.

Now, does the test failure denote a bug in our refactoring, or does it denote an error in how we modified the tests? This is not easy to determine except by stepping through the tests manually. Thus, the test suite does not have high accuracy.

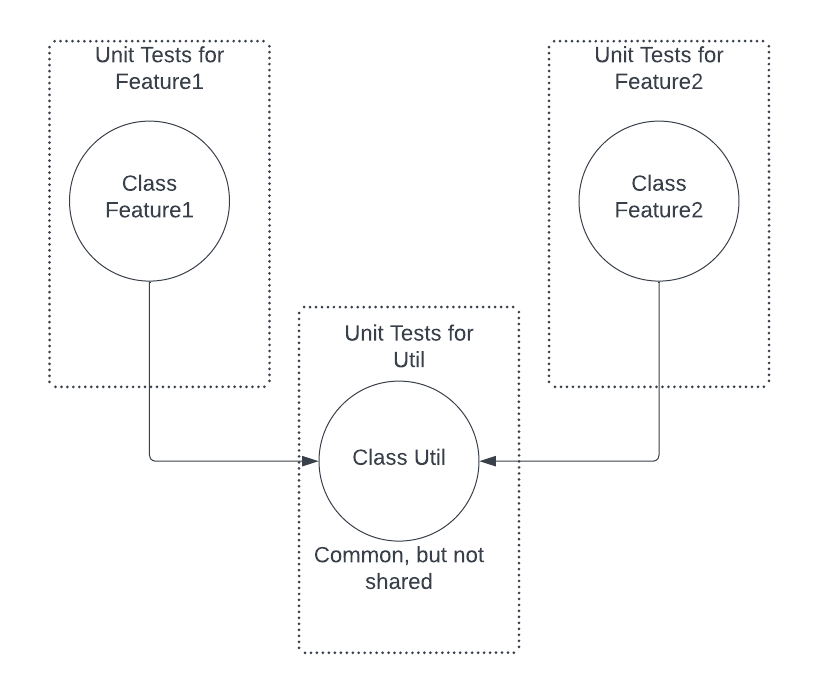

In Detroit

In contrast, according to the Detroit school, the unit tests for Feature1 and Feature2 can use Util as such (without test doubles). The tests for Feature1 and Feature2 look as follows.

If we do the same refactoring across Feature1, Feature2, and Util classes, note that we do not need to make any changes to the tests for Feature1 and Feature2. If the tests fail, then we have a very high signal that the refactoring has a bug in it; this makes for a high accuracy test suite!

Furthermore, since Util exists only to serve Feature1 and Feature2, you can argue that Util doesn’t even need any unit tests of it’s own; the tests for Feature1 and Feature2 cover the spread!

Improved Completeness (around regressions)

In the post on attributes of a unit test suite, I defined completeness as the measure of how likely a bug introduced by your diff is caught by your test suite. I have seen unit tests following the Detroit school catching bugs/regressions more easily, especially when the bugs are introduced by API contract violations.

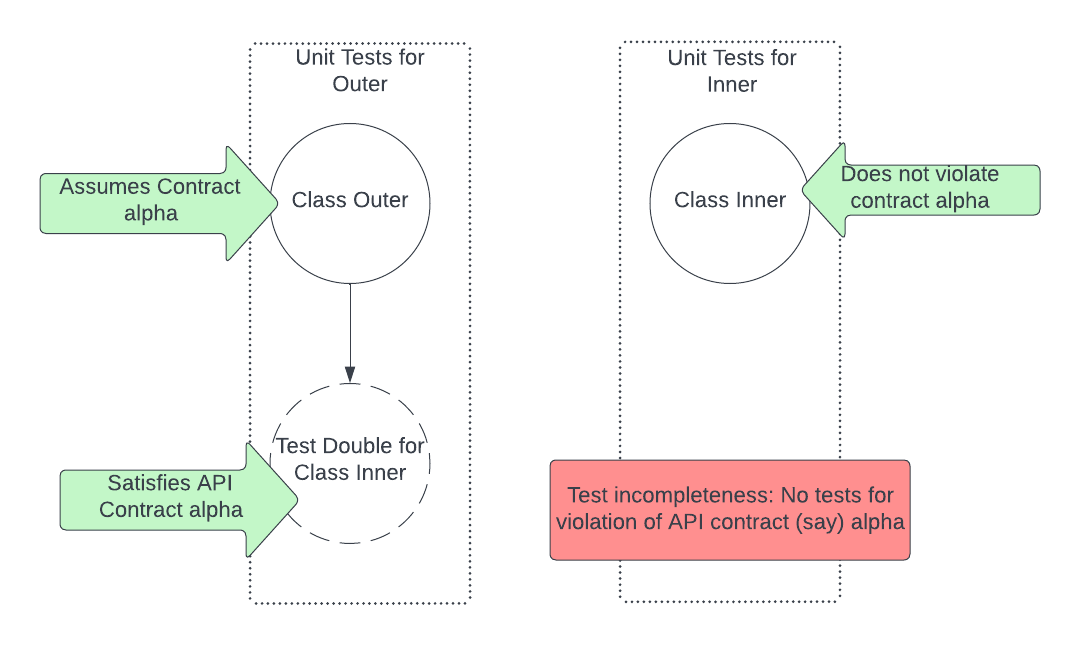

It easier to see this with an example. Say, there is a class Outer that uses a class Inner, and Inner is an internal non-shared dependency. Let’s say that the class Outer depends on a specific contract, (let’s call it) alpha, that Inner’s API satisfies, for correctness. Recall that we practically trade off between the speed of a test suite and it’s completeness, let us posit that the incompleteness here is that we do not have a test for Inner satisfying contract alpha.

In London

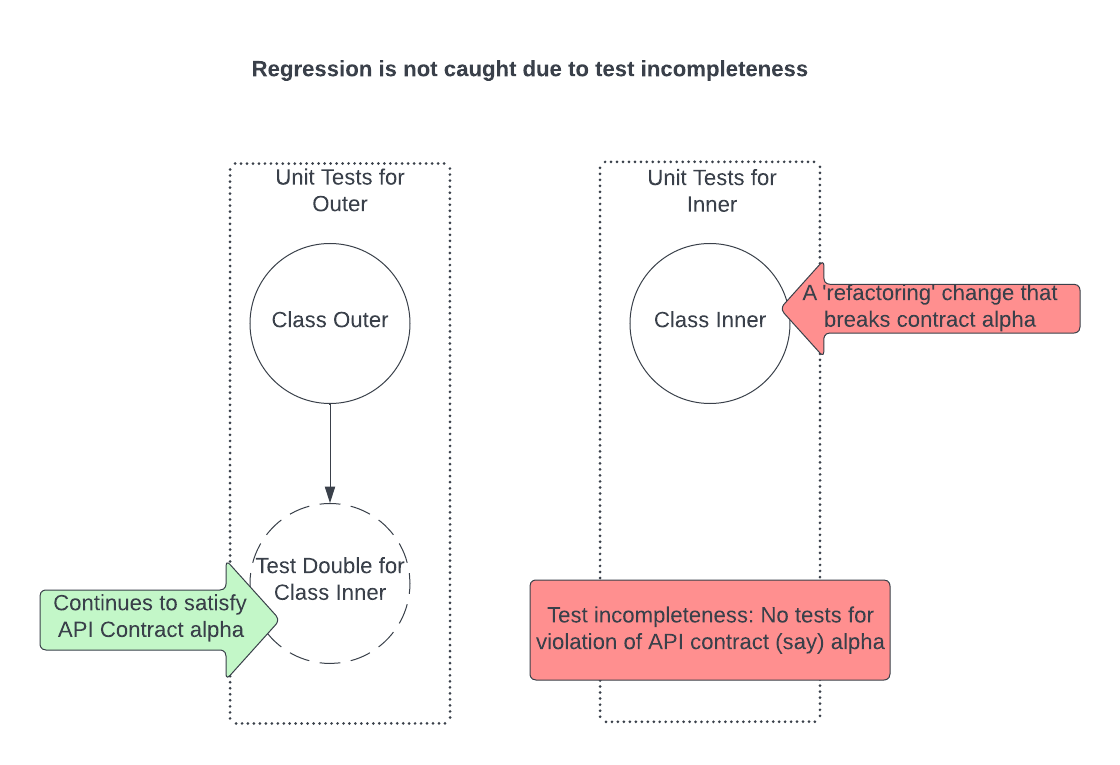

Following the London school, the tests for Outer replace the instance of Inner with a test double, and since the test double is a replacement for Inner, it also satisfies contract alpha. See the illustration below for clarity.

Now, let’s assume that we have a diff that ‘refactors’ Inner, but in that process, it introduces a bug that violates contract alpha. Since we have assumed an incompleteness in our test suite around contract alpha, the unit test for Inner does not catch this regression. Also, since the tests for Outer use a test double for Inner (which satisfies contract alpha), those tests do not detect this regression either.

In Detroit

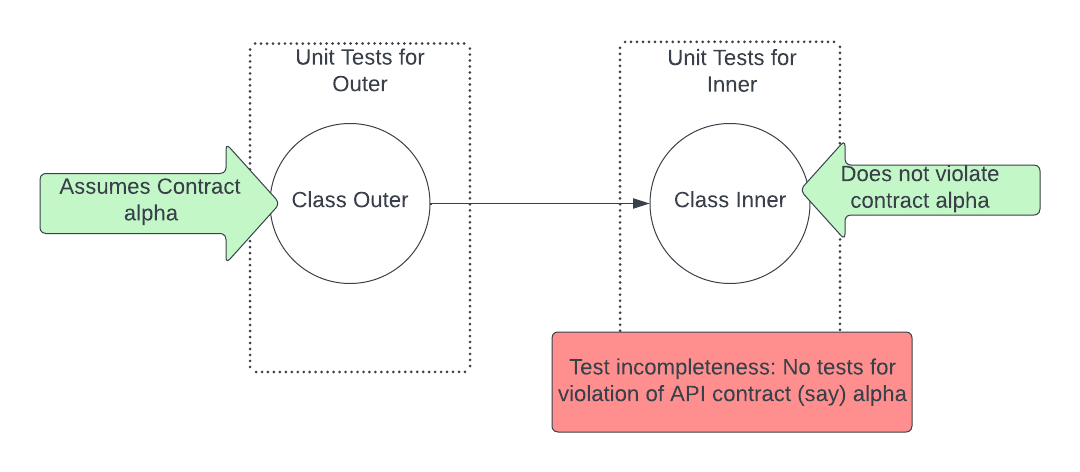

If we were to follow the Detroit school instead, then the unit tests for Outer instantiate and use Inner when testing the correctness of Outer, as shown below. Note that the test incompletness w.r.t. contract alpha still exists.

Here, like before, assume that we have a diff that ‘refactors’ Inner and breaks contract alpha. This time around, although the test suite for Inner does not catch the regression, the test suite for Outer will catch the regression. Why? Because the correctness of Outer depends on Inner satisfying contract alpha. When that contract is violated Outer fails to satisfy correctness, and is therefore, it’s unit tests fail/

In effect, even though we did not have an explicit test for contract alpha, the unit tests written according to the Detroit school tend to have better completeness than the ones written following the London school.

Like it? Share it!