When I first realized my privilege

•

26 February 2022

•

3 mins

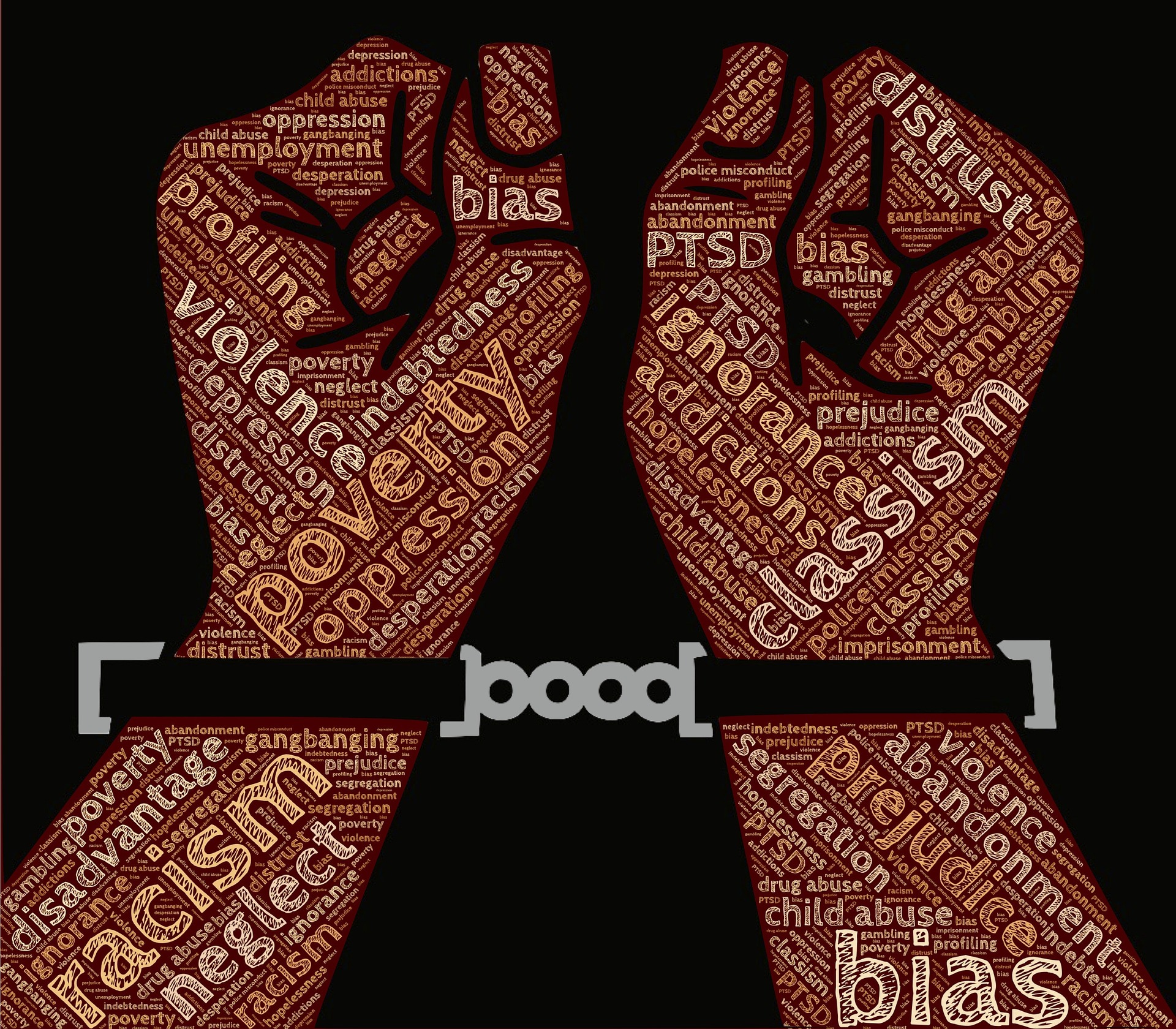

Ironically, a sure marker of privilege is not realizing your own privilege. I grew up being told that I am a Brahmin, which is the highest caste, and that it makes us superior and better than others. Unsurprisingly, I was taught that we were, in fact, an oppressed minority. The government reservations for the so-called Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were often cited as evidence of such oppression. So, naturally, I grew up knowing nothing about the privilege that I enjoyed.

For the first 23 years of my life, I was convinced that everything that came my way was hard earned, and it was despite the oppression against our community. At 23, I was working as a young software engineer in Bangalore. I needed the house deep cleaned, and a contractor said that he would send a couple of people over who would take care of it for us. I was about to get my first glimpse into the privilege that I had enjoyed all my life.

The two people that the contractor send over were completely clueless. They had no idea how to go about the job. They showed up empty handed and asked us what they should be using to clean the house. They required constant supervision and direction, and it consumed most of our time, and defeated the purpose of hiring them in the first place. By the end of the day, less than half the work was done, I was completely frustrated.

It is important to mention that these two folks’ work ethic was never in doubt. They worked as hard and diligently as you could be expected. They were from a village some hours away, quite illiterate, and desperate for work. They hadn’t seen houses in cities before, and so no idea what is involved in the upkeep of a proper house. They probably lived in shanty small houses, and this was all alien to them.

Coming back to the main story, it was close to evening, and very little of the work was done. At this point, the they said that they had to leave because if they didn’t leave right away, then they’d miss the last bus to their village and they’d have to walk home. So if we could pay them, then they will be on their way (and settle the account with the contractor later).

I was pretty upset at this point, and I told them that they hadn’t completed even half the work, and so I’ll pay them only half. They just looked at each other and simply nodded at me. They had this look of someone who has always been helpless and has resigned themselves to this fate for so long that they couldn’t imagine life any other way. I saw all of that, and but my frustration overrode that, and I gave them just half the agreed upon amount and sent them their way.

As soon as they closed the gate behind them, I felt incredibly sorry for them. It wasn’t their fault that they were not skilled. It wasn’t their fault that the contractor sent them our way. And us paying them just half the amount simply means that the contractor will take a larger cut of the money. Despite all of that, all they did was meekly nod. Next, I felt shame and guilt. Me paying them the entire amount would not make a slightest difference to my finances. I spend more going out with friends on a weekend evening.

All of this took about a minute to register, and I immediately called them back and gave them the full amount that was promised to them.

That look of helplessness and resignation stayed with me a long time. But I simply couldn’t understand it in it’s larger context. For a while, I saw this as a fault in their character that will get them swindled, and almost felt good about me not being one of the many who cheated them out of what they earned. Nonetheless, this event stayed with me, as I learned more, I kept recasting that experience with new sociological lenses. It took me years to recognize it as a natural consequence of multi-generational societal oppression, and with that recognize my own privilege.

Like it? Share it!