When should you build for survival?

Srikanth Sastry

•

21 August 2019

•

7 mins

</figure></div> –>

Previously, I wrote about building for survival vs. success building for survival vs. success. Briefly, when building for survival, your only goal to get the product working for the specific usecase, and in contrast, when building for success, you are building to solve a bigger class of problems within the broader context of your solution space. In this post, I will talk about when you should be build for survival, and when for success.

A Straw Man

On the face of it, it seems like an easy answer: "build for survival, when survival is at stake; otherwise, build for success." But unfortunately, that answer hides a multitude of assumptions, and oversimplifies the real-world within which the software development process operates. So, let's first breakdown the assumptions, and then address the oversimplification.

The assumptions

The first assumption here is the notion that we have a common understanding of what it means to say that a project/product's "survival is at stake". And the second assumption is that building for survival in all such cases will actually help.

Is your survival at stake?

Let's examine the first assumption: we can agree on what it means for survival to be at stake. Sure, in the extreme cases, we can all agree on this notion (e.g., a startup has a runway of 6 months, and additional funding depends on delivering an alpha in 3 months), but moving past that, things become a lot more subjective.

Consider a new project/product incubating within a well established company such as Facebook or Google. Is it's survival ever at stake? How about a project that involves building/dismantling infrastructure with a fixed, slightly aggressive, deadline; would it's survival be at stake? The answers to the above questions are not always obvious, and they can be different depending on who you ask. They can differ depending on where you are in the organizational hierarchy; it can even differ among developers within the team.

Ok, so your survival is at stake. So should you build for survival?

Now on to the second assumption: when survival is at stake, building for survival is actually the right thing to do. Again, there are some obvious cases where this is the right call. What about a case where the survival of your medical diagnostic software is at stake; would building for survival actually be the right thing (given that 'break things' is a corollary of 'move fast')? How about when you realize that you were a little too optimistic about what the product could accomplish with the limited resources you have; is building for survival still the right thing (ask Microsoft about Windows Vista)?

The oversimplification made here is that we only ever have two choices: survival, or success. This is almost never the case. You can almost always negotiate. You can negotiate on deadlines, on scope, on resources, on expectations, and on outcomes. Without taking all of the above into account, the discussion of survival vs success is meaningless.

So, when should you build for survival vs success?

While you have to evaluate every situation independently and holistically to determine which approach is the right one to take, here are some rule-of-thumb symptoms that suggest that you should be building for survival.

You are resource constrained, and failure is an option

When you are resource constrained, then there is a good chance that you cannot afford the time/effort/resources that a principled approach to software development demands. Recall, that in such a case, I talked about renegotiating the original parameters and expectations. However, they are not always negotiable. (E.g., you might have only a few months' of runway, and your investor might not be willing to fund you in case of milestone slippage.) In such cases, failure becomes a better option than renegotiation (almost vacuously). Here, building of survival makes sense.

Your environment is highly uncertain

High uncertainty is often a good trigger to build for survival. High uncertainty often requires you to 'fail fast'. If you are working on experimental technology, or on nascent problem spaces, there really isn't much to grok without actually building something and test things out. In other cases, it might not be possible to know if you are solving the right problem; this happens often when your customers tend to "know it when they see it".

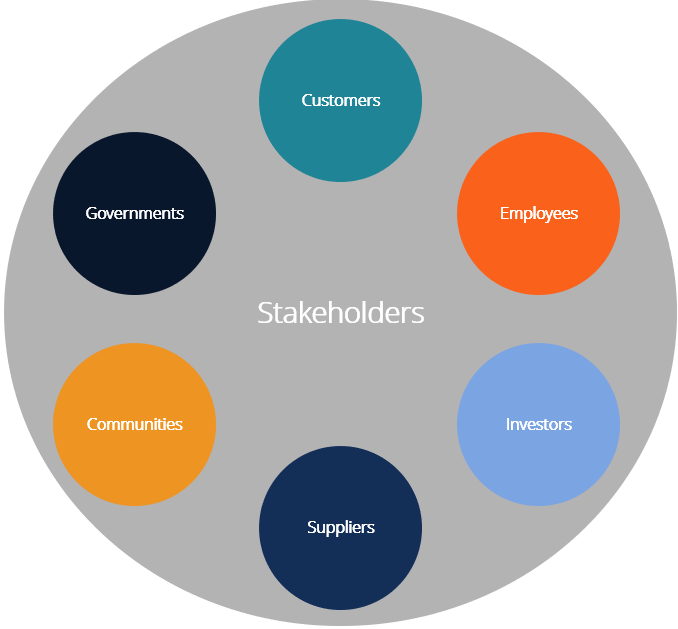

Your survival is more important than stakeholders' risks

This one is less obvious. It could well be the case that your survival is at stake, you are resource constrained, and there is no negotiating. However, there still are situations when you should not build for survival. One big situation is when the stakeholders' risks trump your survival.

The most egregious example I can think of is in medical technology. If you software you are building is for (say) medical diagnosis, and a wrong diagnosis can mean the difference between life and death of a patient, then you should never, ever, ever build for survival. From here, you can extrapolate to all other situations where your stakeholders' risk outweighs yours.

You are solving a one-time problem

This one is tricky, because solutions to one-time problems have a nasty tendency of sticking around a lot longer than they should. However, in principle, if you are writing software that is going to be used just once, and then discarded, then you should consider building for survival. However, please ensure that that software will NOT persist past it's primary use. Incidentally, if your work involves building prototypes and proof-of-concept works, then you are almost definitely building for survival.

There are multiple ways to enforce this: (1) do not put it into version control at all, (2) put the code in a new repo that is nuked on a timer, (3) prevent importing modules from this codebase to anywhere else, etc.

Can you think of any other situations where building for survival is warranted? Let me know in the comments.

Like it? Share it!